Portada interior por: Johanna

Vogelsang, Las Vegas.

Partitura

Serie Músicos

Venezolanos de Vanguardia 2 Velorio Ritual, Caracas:

Fundación Vicente Emilio Sojo, 1995. Depósito Legal: CP 158951.

Disponible directamente del autor.

PDF

Estreno en el

Crane New Music Festival, Potsdam College-SUNY, NY,

Estados Unidos, 1993.

CD Mundos - Emilio

Mendoza. Caracas: ArteMus, 1998. Disponible

directamente del autor.

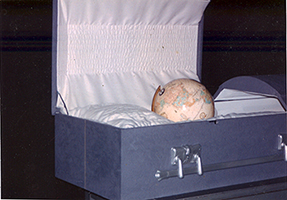

Sobre Velorio Ritual:

El

presente velorio se centra en la posible desaparición futura de

nuestra especie humana. Considerando que el colapso final de los

planetas y estrellas es inevitable con la expansión del

universo, nuestra especie humana puede tener todavía una muy

larga vida por disfrutar. Sólo, por supuesto, si no persistimos

en acelerar nuestra muerte inminente al destruir el único hogar

posible en el universo. Esta composición está enfocada en una

celebración ritual, es un velorio anticipado de nuestra posible

extinción. Puede servir como un recordatorio de este riesgo,

ofreciendo un espacio para reflexionar sobre las maneras que

podemos contribuir en prevenir una desaparición prematura de la

humanidad, la extinción final de la vida misma.

Los velorios son momentos especiales en nuestra

sociedad donde todos nos reunimos, callados o hablando en voz

baja, detenemos nuestro día a día con los apuros vivenciales,

el tiempo se alarga y nos ponemos a pensar y recordar sobre el

difunto que velamos, sobre la familia, amigos, seres queridos,

sobre la vida, sobre los valores que conservamos como grupo de

seres. Este ritual de velorio es un tiempo que nos aporta la

música para soltar el hilo de la vida y pensar cómo podemos

mejorar la existencia, de nosotros y del mundo donde

existimos.

La música

fue inspirada en dos tradiciones de entierros: Las celebraciones

de los wake-keeping

que el autor asistió durante su investigación de campo en

Kokrobitey, Ghana, África Occidental, septiembre - diciembre,

1981. En este ritual, el cuerpo muerto es velado durante la

noche antes de su entierro, con una fiesta masiva donde coexiste

la ejecución de instrumentos, la danza, cantos rituales y

festivos. El bambuco “Obra Dios por el Hombre” del pueblo de San

Lorenzo, Provincia de Esmeraldas, Ecuador, que es ejecutado en

entierros. Velorio Ritual

puede ser ejecutada en cualquier situación de entierro, real o

de ficción, con objetos o comportamientos de velorio, urnas,

candelabros, flores, incienso, vestidos negros, luces bajas,

anteojos oscuros, bebidas alcohólicas, café, galleticas,

sopita o simplemente como música en un concierto normal

de tipo occidental o en grabación distribuida.

Eventos

importantes, especiales y extraordinarios en nuestras sociedades

se llevan a cabo a través de rituales y la actividad musical ha

sido un compañero constante de ellos, ya sea en ejecución o en

el acto de la escucha colectiva. En muchas culturas del mundo,

la transformación de un ser vivo al estado de muerte se ha

tratado como un paso hacia un lugar diferente, hacia lo

desconocido. El ritual de la muerte, que en esta composición se

asume como un "velorio", es básicamente un ritual de despedida,

resumiendo en este sentido todas las situaciones de entierro. El

ritual de velorio se convierte en un momento de profundidad y

reflexión donde los seres humanos que aún están con vida, se

quedan con la certeza de que la muerte es una vez más presente

como una verdad innegable. En este sentido, la noción de por lo

menos dos mundos como parte de la vida misma se concibe y el

ritual se convierte en el umbral o ventana para el proceso de

pasar entre estos dos lugares de nuestra existencia y

no-existencia.

La música

parece ser capaz de permitir que rocemos emocionalmente ese otro

mundo, donde asumimos que todavía existe el ser fallecido de

alguna manera después de desaparecer del mundo real, resultado

de nuestro terco rechazo del estado terminal biológico que

sustenta la existencia. Por lo tanto, el paso a la muerte puede

ser considerada como una recreación sin esperanza de la

necesidad de vivir. En este punto, la composición Velorio

Ritual, como se explica arriba, trata en última instancia

con la situación de nuestra especie donde nuestro paso hacia el

estado de muerte se trunca por la extinción, es decir, la

condición en la cual todos los seres humanos desaparecen del

dominio de la vida, y la vida misma muere.

Fue estrenada por el Crane

Contemporary Ensemble en el Crane New Music Festival, Snell

Hall, Crane School of Music, Potsdam College-SUNY, Potsdam, NY,

Estados Unidos, 27/4/1993. Recibió la Mención Honorífica, Premio

Nacional de Composición, Caracas, Venezuela, 1992 y fue

publicada por la Fundación Vicente Emilio Sojo (FUNVES),

Caracas, 1995, dentro de la serie "Músicos Venezolanos de

Vanguardia". La producción de la partitura fue posible gracias a

un subsidio de la Research Foundation of the State University of

New York, y a la asistencia de la Office of College Relations,

Potsdam College - SUNY, Potsdam, NY. Su grabación apareció en el

disco compacto de la Sociedad Venezolana de Música Contemporánea

SVMC, 25

Años - Antología de Compositores de Venezuela I, Caracas:

SVMC, 2002.

Está

dedicada a mi tío Ing. Jaime Mendoza quien me ayudó durante mis

estudios de doctorado en Washington, DC, con una beca de $150

mensuales. Una coincidencia estraña ocurrió cuando la partitura

recién impresa fue recogida de la imprenta en Caracas, 1995, a

las 8:00 am y recibí una llamada luego de cargar las cajas en el

carro, que mi tío había muerto y en el mismo día era el entierro

de mi tío. Llevé las cajas a su velorio justo a tiempo y pude

colocar la primera partitura dentro de la urna cuando iba a ser

descendido a tierra. ¡Gracias, Tío!

About

Ritual Wake:

The present wake is focused on the possible

future disappearance of our human species. Considering that

the final collapse of the planets and stars is unavoidable

with the expansion of the universe, our human species may

still have a very long life to enjoy. Only, of course, if we

do not persist in accelerating our ultimate death by

destroying our only possible home in the universe. This

composition is focused on a ritual celebration, an anticipated

wake for our possible extinction. It may serve as a reminder

of this risk, providing a space intended to devote some

thoughts on the ways we may contribute to prevent a premature

disappearance of mankind, the ultimate extinction of life

itself. Wakes are special moments in our society when we all

get together, silently and speaking softly, stop our everyday

lives with existential troubles, time lengthens and we start

to think and remember about the deceased one, the family,

friends, loved ones, about life and the values we hold as a

group of human beings. This ritual is a time which music brings to us in

order to release the thread of life and to think about how we

can improve our

lives and the world in which we exist.

The music was inspired by two burial traditions:

Celebrations of the "wake-keeping" that the author attended

during his field research in Kokrobitey, Ghana, West Africa,

from September to December, 1981. In this ritual, the dead

body is veiled in the night before his funeral, with a massive

party where coexists performance of instruments, dance,

rituals and festive songs. The bambuco "Obra Dios por

el hombre" of the people of San Lorenzo, Province of

Esmeraldas, Ecuador, which is performed in burials. Ritual

Wake may be performed in any burial situation, real or fictional,

with objects or behaviors typical of funerals, coffin,

candles, flowers, incense, black dresses, low lights,

sunglasses, alcoholic drinks, coffee, crackers, soup or just

as a normal, western-type of concert or distributed recording.

Important and extraordinary

events in our societies take place through rituals, and

musical activity has been a constant companion to them whether

through performance or in the act of collective listening. In

many cultures of the world, the transformation of a living

being to the state of death is treated usually as a passage

into somewhere different, into the unknown. The ritual of

death, which in this composition is assumed as a “wake,” is

basically a farewell ceremonial resuming in this sense, all

burial situations. The ritual wake becomes a moment of

profoundness and thoughtfulness, since the humans that are

still with life are left with the certainty that death is once

again present as an undeniable truth. In this sense, the

notion of at least two worlds as part of life itself is

grasped and the wake becomes the threshold or window for the

process of passing between these two places of our existence

and non-existence.

Music seems to be able of

allowing us to emotionally sense this other world, where we

assume that the dead person still exists in someway after

disappearing from our known reality, as a result of our

stubborn rejection of the terminal biological state that

sustains existence. Therefore, the passage into death can be

considered as a hopeless recreation of the need to live on. In

this point, the composition Ritual Wake, as

explained above, deals ultimately with the situation in our

species where our customary “passage” into the dominion or

state of death is truncated by extinction, that is, the

condition in which all human beings disappear from the

dominion of life, and life itself dies.

It was premiered by the Crane

Contemporary Ensemble in 1993, within the Crane New Music

Festival, State University of New York College at Potsdam, NY,

USA, on the 27th of April, 1993. It received the Venezuelan

National Composition Prize in 1992 and its score was published

by the Fundación Vicente Emilio Sojo (Funves) in the series "Músicos Venzolanos de

Vanguardia," Caracas, 1995. The production of the score

was possible by a grant form the Research Foundation of the

State University of New York and the assistance of the Office

of College Relations, Potsdam College - SUNY, Potsdam, NY. It

appears in the first CD of the Venezuelan Society for

Contemporary Music (SVMC), "25 Años - Antología de

Compositores de Venezuela I," 2002.

It was dedicated to my uncle

Ing. Jaime Mendoza who helped me financially during my

Doctor's Degree studies in Washington, DC, with $150 monthly.

A strange coincidence occurred when the score came out from

the printers in Caracas in 1995, and I went to pick it up at

8:00 am, and after putting the boxes in the car I was called

and informed that my uncle had died and that he was to be

buried on the same day. I took the boxes straight to his wake

and the first printed score from the box was put inside his

coffin just in time before he was lowered down to earth. Thank

you, Uncle Jaime!